By Rodolfo Elías.

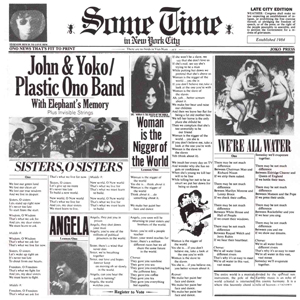

Some fifty three years ago, John Lennon released the infamous —according to many of his detractors— album Some Time in New York City, which he co-produced with Phil Spector. A commercial and critical flop that was controversial in multiple ways: the lyrics, the cover design, the music, the collaboration between John and Yoko. It gave John a bad name (at least for the time being) and contributed greatly to the threat of his deportation from the USA.

The times they were a-changing. And by 1972 John Lennon had gone from being one of the Fab Four —adored by millions of girls and admired by an equal amount of boys around the world— to scruffy John, with the long hair and unkempt beard; whose passionate activism and radical ideas were being received, at this point, with contempt by many people. It had been almost a year since he established himself in New York City, with Yoko in tow, of course.

Upon his arrival in the USA, John was hit with an intense wave of social awareness. Those turbulent years in America with Vietnam, Watergate, and the Cold War as constant reminders of the ineptitude and ruthlessness —by commission or omission— of the people running things in the world. Impossible for any conscientious, decent human being to ignore; and John Lennon was a conscientious individual. Not too long afterward he was approached by the activists Jerry Rubin and Abbie Hoffman, who talked him into joining forces with them on their disruptive endeavors against the establishment. Lennon, who had already been vocal about the irregularities in the world, decided to put his money where his mouth was.

Thus, on top of all the rallies and events for different causes he attended, John thought of making an allusive album, meant to be accompanied by a tour. At this point he had already built a reputation for his hands-on involvement in political and social causes. Moved by what he saw in the streets of New York, what he heard in the news and what he read in the newspapers, John Lennon got busy and started working on what would be Some Time in New York City. In his usual way of calling things by their name, he gave us a graphic account of the things that were happening around him. And he nailed it right in the head, as he did when taking matters into his own hands and challenges head-on. The album was released in the United States in June of 1972.

Upon listening to it, people were outraged by its political and social activism, right off the bat. In a display of pettiness and intolerance they made such a big deal, blowing things completely out of proportion. Even a good number of fans, on both sides of the Atlantic, weren’t sympathetic at all with John’s new release. The critics also lambasted it viciously and knocked the album’s in-your-face approach, the lyrics’ straightforwardness and, pretty much, everything. Others had done it before, but this time it was John Lennon; and they seemed to have had enough of him at this point. Some critics even found the lyrics simple minded, superficial, unsophisticated, and even childish.

But they missed the point completely. The same way they had missed the point when they misunderstood a piece like “Cold Turkey”, a couple of years back. Is that some form of callousness or what? People were so antiestablishment a couple of years earlier and now they were finding fault with one of their spokesmen for saying things the way he did. In their critique of the album and its author, critics used terms and epithets full of bile, which shows they weren’t unbiased but that they might have had an actual agenda.

Was it just bad timing, because Some Time in New York City came out at a time when protest music wasn’t cool anymore? The fad had faded away and the performers that made a career and a fortune selling protest music had moved on to new things, and decided to go with the flow of the new music, following the rules of capitalism. Even Greenwich Village —which was where John lived during this time—, whose coffeehouses housed some of the most prominent folk and protest music singers ten years earlier, had been vacated by its most prominent figures. And, here we had John Lennon taking risks and facing new challenges, as he kept lending his voice to peace and human rights, not as a career move, but as the real pursuit of a cause.

People seemed predisposed to Some Time in New York City and had a dismissive attitude right at the outset. Had this record been made by someone else, they would have been more receptive and better disposed. At this point it was clear that Lennon’s political and ideological stances were affecting record sales and also the concept that some people had of him. Especially the American people, who didn’t see it right for a foreigner to attack their institutions, even in the person of a greatly corrupt president like Tricky Dick.

Americans wouldn’t suffer John Lennon attacking their institutions and their reaction was harsh. Part of it was the biting, antiestablishment lyrics and the bluntness with which some concepts are presented (e.g., the use of the “N” word and allusions to drug use) that weren’t embellished with the poetical language and literary landscapes of folk music. Which explains why Sixto Sugar Man Rodriguez’ career —which started around that time— didn’t take off; a son of immigrant parents who sang about social inequality and drugs, whose songs also had biting, antiestablishment lyrics that weren’t embellished with a poetical language and literary landscapes.

Some critics referred to Some Time in New York City as the worst album by a rock star, which is ludicrous. Rolling Stone magazine, that was supposed to be socially conscious —and on John’s side— also attacked it ruthlessly. Stephen Holden wrote: “Only a monomaniacal smugness could allow the Lennons to think that this witless doggerel wouldn’t insult the intelligence and feelings of any audience.” Well, only a monomaniacal smugness could allow a supposedly professional music critic to write that about an album like this. And, by looking at Holden’s credentials and academic background, it is very obvious that his critique was biased and meant to be as derogatory as possible; he called the album “incipient artistic suicide.” But John Lennon had more than one artistic life.

New Musical Express (NME) writer, Charles Shaar Murray, wrote: “The self-immolation of John Lennon’s musical/political credibility via the sublimely fatuous ‘Some Time In New York City’.” He really seemed to have it out for John, because eight years later he would write about Double Fantasy: “The album celebrates their mutual devotion to each other and their son Sean to the almost complete exclusion of all other concerns. Everything’s peachy for the Lennons and nothing else matters, so everything’s peachy QED. How wonderful, man. One is thrilled to hear of so much happiness.” And Murray wishes “that Lennon had kept his big happy trap shut until he has something to say that was even vaguely relevant to those of us not married to Yoko Ono.”

In a 2010 article for Uncut magazine, Gary Mulholland refers to Some Time as part of a five-year process of self-sabotage, asserting that the album is “a contender for the worst LP by a major musical figure, its list of ’70s left-wing clichés hamstrung by the utter absence of conviction within the melodies and lyrics.” And he adds: “From there, you can almost taste the mixture of anxiety, exhaustion and hard liquor that lie behind Mind Games, Walls and Bridges and Rock’n’Roll as Lennon fought almost as hard to screw up his marriage as he did to win his Green Card.”

Gary Mulholland, by the way, is the same critic who gave only two stars to Walls and Bridges (as well as to Some Time in New York City), which happens to contain John’s first number-one hit, “Whatever Gets You Thru the Night”, and the beautiful “#9 Dream”; along with gems like “Scared”, “Going Down on Love”, “Steel and Glass”, and “Bless You”.

The writer that was more relaxed in his critique of the album was Dave Marsh, who wrote for Creem magazine in August 1972: “I’m listening to a tape of the new John and Yoko LP. If you thought, as I did, that Sometime in New York City was going to be a complete disaster, cheer up. It’s not half bad. It may be 49.9% bad, but not half.”

Well, no matter what naysayers want to make us believe, I think Some Time in New York City is daring, ambitious and very much in tune with its times. And by making this album, John Lennon wasn’t trying to be Bob Dylan nor emulate him. Even during the time when he was deliberately “imitating” Dylan —making songs à la Dylan—, Lennon would keep his own irreverent style and distinctive trademark wit, giving songs his own twist; because he was doing it his own personal way.

John Lennon’s way of writing protest songs was very different to Bob Dylan’s. And he never tried to get out of the pop/rock song format, with the bridges and choruses, which Dylan didn’t do. Bob Dylan, for the most part, followed lineal monotones in his songs, with a chorus, which could be tedious at times. This is what Sting said about bridges in songs, in his interview with Rick Beato: “To me the bridge is therapy, you know. You set a situation out in a song: ‘My girlfriend left me. I’m lonely.’ Chorus: ‘I’m lonely.’ You reiterate that again. Then, you get to the bridge. There’s a… there’s a different chord [that] comes in. ‘Maybe she’s not the only girl on the block. Maybe I should look elsewhere.’ And, then, that leads to a… that viewpoint leads to a key change… ‘Things aren’t so bad.’ So it’s kind of therapy. And that’s therapy for me; the structure is therapy.”

John’s style of protest was also different. You can call John Lennon naive, idealist or whatever, in his way of protesting; but you can’t call him a phony. Because he got in the trenches —as he knew them— in very tangent and practical terms. Whereas Bob Dylan’s was more of a media directed protest, even in his heyday; unsubstantial in practical terms.

The documentary One to One: John & Yoko gives us an itinerary of John’s life during the planning and performance of the two-show benefit concert “One to One” that he played at Madison Square Garden, for children with disabilities at Willowbrook state school. Which it was also around the time when he made Some Time in New York City.

And one of the good things about the documentary is that it puts John’s arrival to New York City in context with the times in America. All the political and social unrest, Vietnam, Attica State riots, the shooting of the presidential candidate George Wallace, and Watergate. It gives us the big, real picture of John Lennon, whose activism went beyond just writing protest songs. John was really invested, and the proof of that was the benefit concerts (two in one day) that he did, which were intended to be part of the One to One tour.

Those two concerts also show us John Lennon as a live performer after the Beatles, with that kind of raw energy —very in line with rock music ethos— displayed only by some of the greatest performers. Led by the moment, Lennon gives live music his own twist and makes it more intimate —real flesh and bones—, adding more intent to it. It’s like the difference between Billy Joel and Elton John. A Billy Joel live performance is cleaner and more like the record; while Elton John’s is more alive and fleshly. I love it when Lennon is singing “Come Together”, in one of the Madison Square Garden shows, and he goes: “Come together, right now. Stop the War!”

I am doing now a partial review (only studio music and songs attributed to Lennon/Ono) of Sometime in New York City. An album that, in spite of the fact that was made on the go —at a faster pace than usual—, with unfamiliar musicians, unfamiliar environment, an adopted country, and days of revolt, it was pretty good. An artist needs the proper conditions for the mastery of his work and John Lennon couldn’t get that for the recording of this album.

So, keeping in mind the conditions in which Some Time in New York City was made and its theme, John Lennon gave us a real gem. He was out of his comfort zone in all respects: emotionally, creatively and mentally; and musically, because he was adopting a different style. He was out of his league and his music somehow was going to suffer. Nevertheless, he was also at his most daring and adventurous, with music that was hard to make, not only due to the political and social contents, but also the delicacy of his situation in the US. John Lennon was still reacting to everything that was happening around him and he was a natural at that. And, if you really pay attention, you’ll see that the songs are well put together and they all have intention and purpose; no idle tunes nor fillers.

We’re starting with “Woman is the Nigger of the World”, a no-brainer for all the bleeding hearts. A rocker with the rawness of a cabaret number, if that means anything. Is it just the use of the “N” word that critics have a problem with? Because it depicts a common scene in a lot of the homes in the 70s, where macho man came home from hanging with the boys and exercised his power on a woman that was supposed to be submissive. Also, the way women were treated civilly and at the workplace. The lyrics are on point and well articulated, even though some critics found them simple-minded. The brass and electric guitars go very well together. A wonderful thing about this tune is that there are at least two live versions of it available: the one in the One to One concert and an appearance on Dick Cavett Show. Both performances attest to John Lennon’s vocal prowess.

“Attica State”. A bluesy, well-crafted tune with a cool guitar riff and biting lyrics, against the great authoritarian empire —with the police, judges, and media at its disposal— that build prisons to keep people down, which goes in line with what Michael Foucault covers in his book Discipline and Punish. But this wasn’t 1964, and baby boomers were now married, had started families, and acquired responsibilities. And raising kids had changed their perspective on life and politics; they had to be prudent now in their assessment of government’s duties. In other words, they were more conservative and less rebellious. So, they didn’t really care for a tune like this.

And we have “New York City”, the song that chronicles John’s experience in the Big Apple. Like a continuation of the “Ballad of John & Yoko”, but it goes from standing in the dock at Southampton to standing on a corner in New York City. Another rocker, inciting you to ride the boogie; like a breath of fresh air for the people who were trying hard to like the album. Also a very well crafted tune, with real swagger that brings us Beatle John back and his great ability to make some good rock ‘n’ roll music.

Next, is “Sunday Bloody Sunday”, one of the most controversial tunes in this collection. Straightforward and crude in its approach, with some incendiary lines. Very clear about John’s anger and outrage; and, also, very honest. A solid, well constructed —that opening drumbeat— rocker, musically in tune with the kind of music that Bob Marley was making along the same lines, protesting the intrusion of imperialistic powers. Some critics found it simplistic and even found fault with the musical arrangements, but this is no wishy-washy tune; it has real purpose and craft. As opposed to U2’s “Sunday Bloody Sunday” that is compromised. Ironically, U2 are Irish, but in the name of being conciliatory, their song doesn’t really say anything about Bloody Sunday; not even as a metaphor. And, by the way, U2 took Lennon’s idea of opening the tune with a drumbeat.

“The Luck of the Irish” is the second song in this album that, flat-out, enraged some people; even more so than the previous tune. It was called all different things, “impotent”, “unwelcome aberration”, and even “sentimental.” But it also got praise from different fronts; some people called it “gorgeous and underrated,” “impressive if flawed”, “clever.” This shows clearly how some critics where out to get John and find fault with everything he was doing. They insisted that the song was stereotypical and clichéd lyrically, but I think it was done like that on purpose; to make a contrast between the melody and the biting attack on the invaders. Beautiful, folkish melody.

Then, comes “John Sinclair”, the song that can be remembered as a pass for freedom, whose authorship is accredited to John alone. It was after a rally that John Lennon attended, where he sang the tune, that John Sinclair —a professor turned activist, who was given ten years in prison for offering two joints to undercover cops— was set free from prison. I don’t think there’s any fault to be found with this down-to-earth, unpretentious tune that is doing some practical activism by asking for John Sinclair’s release. You can hear the influence of this song, at least in the melody, on Bob Dylan’s “Buckets of Rain”, which comes in one of his best albums, Blood on the Tracks. Before John started singing the song at the aforementioned rally, he quipped: “Okay, so flower power didn’t work. So, what? We start again.”

“Angela” is the last song in the album done in co-authorship with Yoko. Honoring activist Angela Davis. A song of redemption, well projected in the melody and the chorus; with some words of hope and appreciation that reaches a sort of climax, very well conveyed by Phil Spector’s Wall of Sound. There’s an instrumental break with a beautiful organ solo —very soothing—, which seems to convey that everything will be all right.

And last, but not least, “Cold Turkey”. The tune that had been released as a single in October of 1969. A well-crafted rocker, with real edge and a pungent message about being helplessly addicted to heroin, which was already becoming a real issue at the time, as soldiers were coming back from Vietnam all strung out on it; and it was going mainstream. This tune really deserved a better fate, to be up there among the great rock songs of the era.

Something I want to emphasize here, is that on Some Time in New York City all John’s songs are well defined, strong numbers. Even more solid than some of the songs in his following two original albums. I actually think that “New York City”, the only song that got general praise, is the weakest number in the album.

There are live performances of all these songs on Youtube (Crisler Arena concert, of December 10, 1971, is one of them), which puts them in a different light. Because it allows us to see them for what they are, as solid tunes that are not just the product of a rampage in the recording studio, but music that was really meant to be; music that comes alive and materializes well when played with a live band.

If John Lennon wouldn’t had burned a bridge with Frank Zappa (by ripping him off, after they jammed together, and including some of the live music in the record, accrediting it to John and Yoko), Zappa would had probably endorsed Some Time in New York City. Which, in turn, would had granted Lennon some legitimacy in the progressive and underground music circles.

If he was getting back at the system, for treating him the way it did; if he was being naive and shooting from the hip; if he was reckless as an artist; or, if he was just being himself, with Some Time in New York City John Lennon gave us an honest and heartfelt collection of songs. And, with that, he made a far greater contribution to music —and activism— than people want to concede. At that point his image as Beatle John had faded significantly in people’s memory and he didn’t have the guidance of a good manager to tell him how to go about presenting it to the audience. But the legacy is there.

By playing with Zappa, John Lennon proved himself to all the people that didn’t think he was avant garde enough, or that thought of him as just a pop musician. If Zappa agreed to jam with Lennon, it’s because he saw him at his own level one way or another. I actually find it hard to believe that it was John’s idea of getting over on Zappa that way. Knowing Yoko’s modus operandi, I’m more inclined to think that it was her thing. But John went along with it, which makes him just as guilty.