By Rodolfo Elías

Early December marked the 60th anniversary of a record that signaled a turning point in modern music. On the fateful night of February 9, 1964, when the Beatles made their appearance on the Ed Sullivan Show, they didn’t really know what that would entail; even after they kicked off Beatlemania with their apotheotic performance and became the Fab Four. And even after the shooting and the subsequent success of their first movie, A Hard Day’s Night, the boys didn’t know if they were in for the long ride.

The distributors of the movie in New York had their concerns and doubts about the Beatles phenomenon. And they told producer Walter Shenson that they had to ask “a very important question.” The question was: Will the Beatles last? They were thinking about putting out as many prints of the movie as possible, because they wanted to get their money back, “before the Beatles fade away.”

In December of 1964 they released Beatles for Sale, an album that got out of the usual rock ‘n’ roll and pop format. The boys were already starting to think outside the box, getting into what critics considered country (even John thought of it as country music) and some songs that were clearly influenced by Bob Dylan. But it was, actually, the beginning of folk rock. You can hear the effect of tunes like “What You’re Doing”, “I’ll Follow the Sun” and “I’m a Loser” on the Byrd’s music. Especially the direct influence of “What You’re Doing” on “Mr. Tambourine”, the first song by the Byrds to top the charts. Roger McGinn would declare years later: “I’d say the Beatles started folk rock, because they’re the ones who inspired me to put folk music and rock and roll together.”

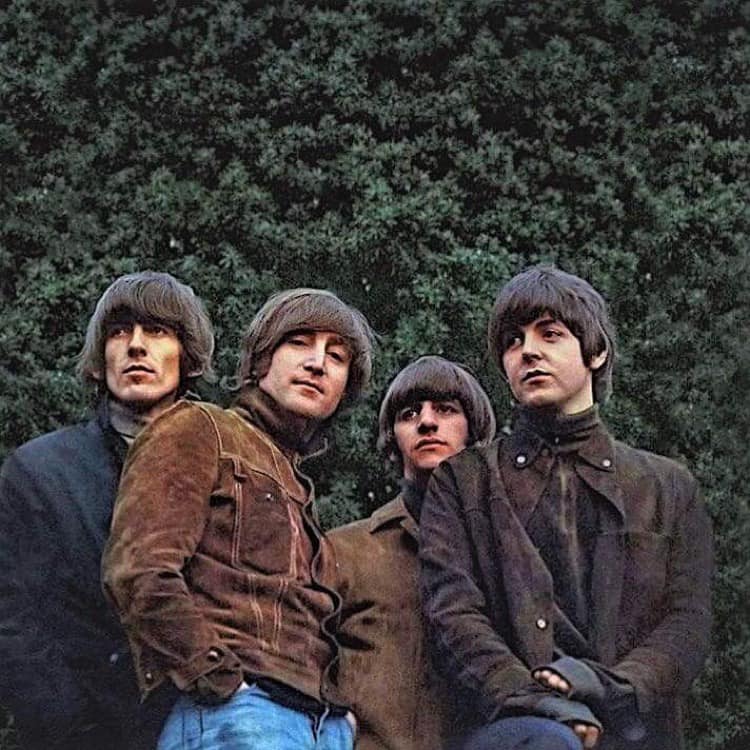

At this point the Beatles seemed pretty solid, at least commercially, if not creatively. But, although they had already given glimpses of their ability to make memorable music with songs like “I’m a Loser”, “I’ll Follow the Sun”, “You’ve Got to Hide Your Love Away”, “Ticket to Ride” and “Yesterday”, out of Beatles for Sale and Help!, it was still a far cry from what they would accomplish at the end of 1965. Enter Rubber Soul.

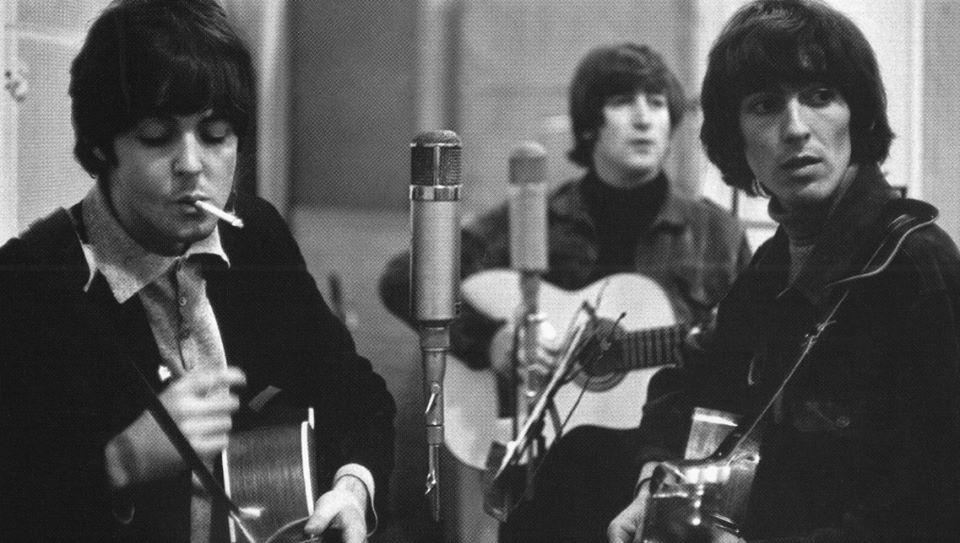

What they started with Beatles for Sale was defined a year later, when Rubber Soul was released —with Help! in between— on December 3, 1965. It’s here where the Beatles really start shining for that versatility that would define their musical expression, because Rubber Soul is pop, rock, folk, country, and even soul. It is also the second album after A Hard Day’s Night to have only original songs, no covers.

In an interview with The Guardian, Brian Wilson said that Rubber Soul was the first album he heard where all the songs “went together like no album ever made before.” The first one to have a real album feel. At another interview, Wilson said about the record’s influence on his music: “We were smoking this marijuana and we were stoned. And Rubber Soul just took me away… Took me away, so I went to the piano and started writing Pet Sounds. It was a moment that lived forever in my heart.”

Those statements by Wilson summarize what every recording musician, with a somehow solid career, felt when they listened to Rubber Soul for the first time. They were taken away by it, in such a way that they couldn’t withstand the impact it caused on them; the bar had been set high and the situation was asking for a change of game altogether. Only the ones that were able to reinvent themselves survived.

I’m going to review ten songs out of the fourteen that appear in the album. For that I selected the ones I considered the most relevant, but emphasizing the fact that every single tune in the record carries its own relevance.

“Drive My Car” is the song that opens the album. A rocker with a hard, solid sound and a cool vibe reminiscent of ska. Very clever, both musically and lyrically, about a girl that is recruiting the author as a driver, although she doesn’t have a car: I got no car and it’s breaking my heart/But I found a driver and that’s a start. The opening guitar riff works as a strong hook that tells you right off the bat that you need to listen to this tune.

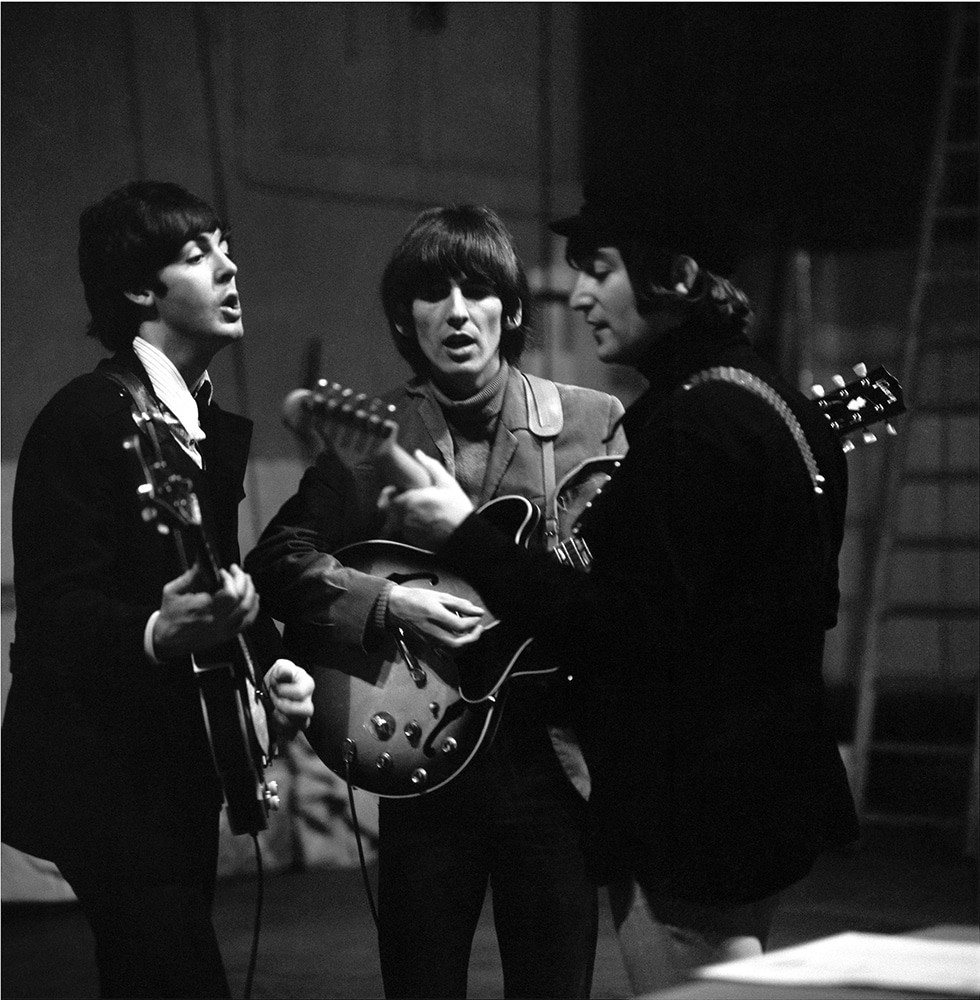

The second tune, “Norwegian Wood (This Bird Has Flown)”, is one of the highlights of the album. Another song, out of three or four, that bears the obvious influence of Bob Dylan. But it stands out for its unusualness, very telling of the Beatles’ aspirations to a more adventurous way of making music. It was the Yardbirds, with “Heart Full of Soul”, and the Kinks, with “See My Friends”, the first bands to make rock songs with a touch of India (raga rock), by producing effects with the electric guitar similar to the sitar and the tambura, respectively. But the strongest innovative aspects of “Norwegian Wood” lie in the fact that the Beatles used an actual sitar (played by George), along with the fact that the sitar here is not meant to evoke an Indian feel or raga sounds. They weren’t so interested in following trends as they were in improving a song.

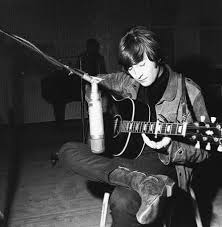

“Nowhere Man” is the next song, also by John. An exquisite three-part harmony piece, with a beautiful and soothing melody —as opposed to the lyrics— and an inspired guitar solo by George, that is not about a girl nor about boys being boys, but about somebody who is trying to find his place in the universe. Deep, isn’t it? Well, that’s where John Lennon found himself at this point in his life, after his encounter with Bob Dylan and, subsequently, with Mary Jane; faced with all kinds of philosophical, existential dilemmas. First, he thinks of himself as a loser; then, he was crying for help; and at this point he realizes he’s on his own, alone on his personal quest.

We get now to “Think for Yourself”, by none other than George. Also a philosophical number, but more playful and encouraging. With a funny chord progression, illustrative of the most pure role that music played in the Beatles’ lives. When they played, they found their purpose in life; hence, the natural candor of their music. In the introduction, the melody tells us quiet a bit about future George and his trademark musical intricacy. And it also illustrates things as to how much this record was different to the music that was being made at the time.

Then, we have “The Word”, by John. A tune about love, with soul undertones, full of artifice. “It’s the word, love”, one of many proverbial expressions — such as “love is all you need” or “love is the answer”— that the “tough” Beatle would use in some of his songs, which sounded so well in his voice. Ringo’s drumming is remarkable, but the execution of every instrument is clever and enchanting, from the piano opening chords to the slick three-part (doubled) vocal harmony. Some critic perceived the influence of two soul classics, Wilson Pickett’s “In the Midnight Hour” and James Brown’s “Papa’s Got a Brand New Bag”, but I think there’s a more direct influence from Bob & Earl’s “Harlem Shuffle” —along with its enigmatic vibe.

And we move to “What Goes On”, a country number sung by Ringo, who also shares co-authorship with John and Paul. The reason I wanted to talk about this number, even though is not really a great tune, it’s because it adds to Rubber Soul‘s originality; because I find it somehow clever; and because it confirms the Beatles’ versatility as musicians and as lyricists. And their influences are shown here clearly as a form of homage, perhaps. In his book The Beatles as Musicians: The Quarrymen through Rubber Soul, Walter Everett talks about George’s rockabilly infused guitar, à la Carl Perkins, and John’s “Steve Cropper-styled Memphis ‘chick’ rhythm part.” I’m writing this a few days after Steve Cropper’s passing, by the way.

“Girl” is next. Again John, with a song that comprises an amalgamation of styles of music and onomatopoeic words that render it a melodic tour de force; which makes for a very clever form of musical expression altogether. The Beatles exploring new, sophisticated forms of lyrical and musical complexity. Although Paul has been trying to claim the following lines, is very clear that they’re John’s, as he would often delight us with philosophical expressions of common lore turned into pop poetry: Was she told when she was young that pain would lead to pleasure?/Did she understand it when they said/That a man must break his back to earn his day of leisure?

With “In My Life”, the Beatles put another song in the grand catalogue of music of all ages that they had accessed initially with “Yesterday”, and of which Paul would be an habitué in the future. A song by John (with Paul contributing with the middle eight), who is making a recount of significant places (though some have changed) and people in his life: some are dead and some are living. 26-year-old John Lennon acquiring an old soul and reminiscing about yesteryear. The melody, the lyrics, the harmony, and that haunting Baroque-style piano solo by George Martin are out of this world.

Next, is George again. “If I needed Someone” is a song where the influence of the Byrds is felt strongly, just like we hear it on “Nowhere Man”. But in this case is more tongue-in-cheek, because George is playing the same game with Roger McGuinn that Paul was playing with Brian Wilson. The jangly guitar à la McGuinn and beautiful three-part harmony vocals. And it has —prominently— ambiguous lyrics, in the fashion of “Norwegian Wood”.

Last, but not least, the infamous “Run for Your Life”. Where John adopts the same threatening stance of “You Can’t do That”. Macho-man, John Lennon, who can’t suffer his woman talking to another guy, is a tough —but lovely— rock ‘n’ roller, in a quintessential rockabilly that gives it just the right idiosyncratic touch. The vocals and the guitars are really cool, contrary to the bleeding-heart critics’ opinions (including John’s) who want to knock the tune down because of it’s lyrical contents; it was 1965, for crying out loud! Thomas Ward nailed it right in the head: “Indeed, the lyric is highly patronising an hopelessly aloof, although Lennon manages to sing it with admirable gusto.” Funnily enough, some people that criticized John for this song would also criticize him as a solo artist for “Woman is the Nigger of the World”.

Rubber Soul marks the beginning of an era —that turning point when rock ‘n’ roll became rock— that gives us the first full view of the Beatles as this innovative band that was a real music-making machine; and they had the purest way of playing and making music. Their music was organized noise, as Frank Zappa once called it, elevated to the most perfect form of art. As musicians, they were an anomaly and all of them had unconventional ways of playing their instruments. But making music seemed to be the most natural thing for them.

The Beatles were no virtuosos, but their music was beautiful beyond virtuosity; because music played the most pure, ludic role in their lives. When the Beatles played, they were children at play. And no other band has ever made —nor will make— music like that.