By Rodolfo Elías.

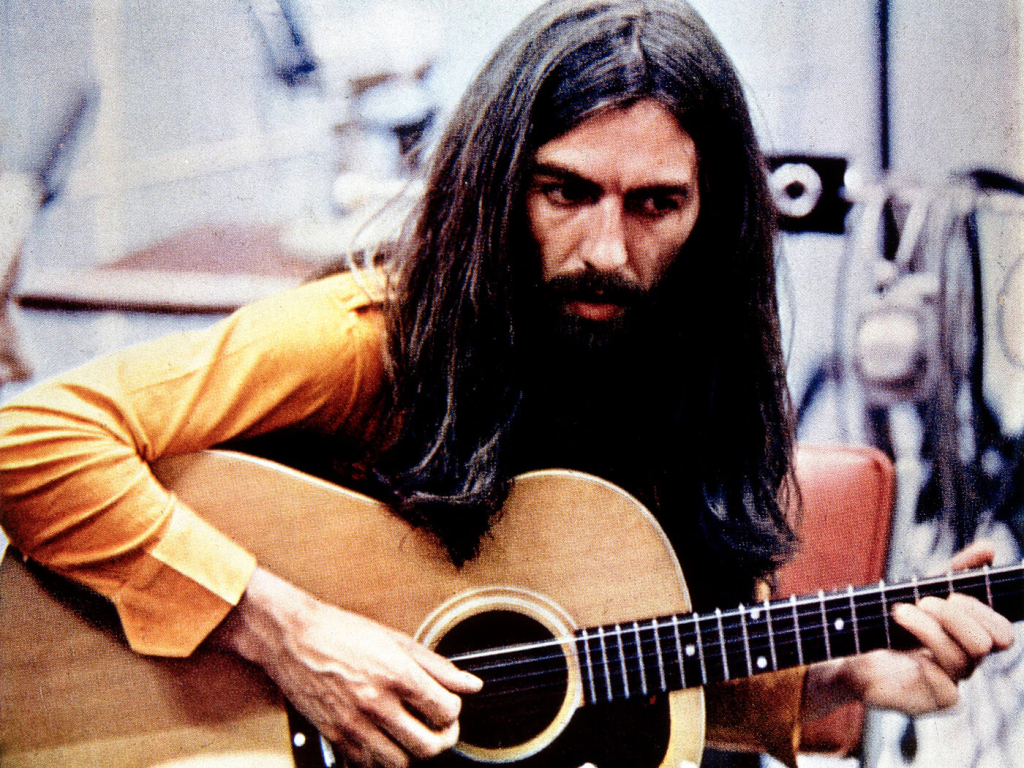

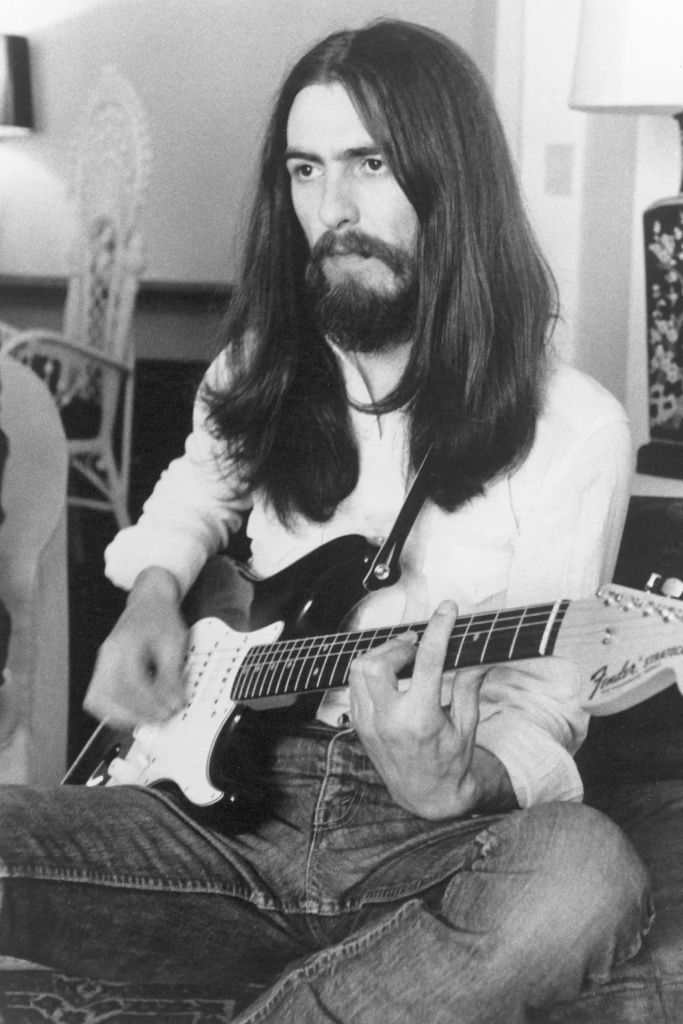

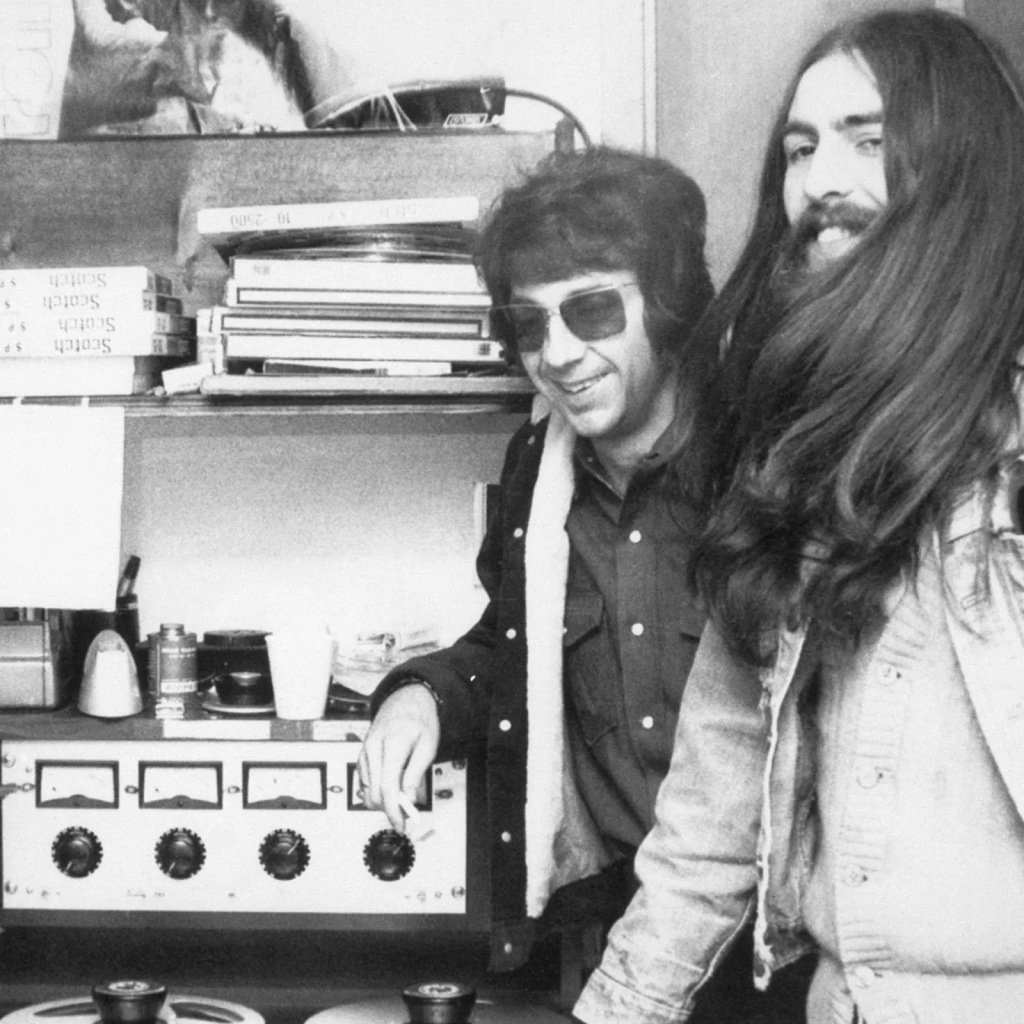

In the Spring of 1970, a bunch of freelance musicians of renown convened in the studio, to see how they could be useful in the recording of an ex-Beatle’s record. The producer would be none other than Phil Spector, who brought along his famous Wall of Sound. Late Fall that year, the album All Things Must Pass was released. And a new star in his own right was born; George Harrison was no longer the quiet Beatle.

It was April 10, 1970, when Paul McCartney walked out on the Beatles, to announce the end of the most cherished musical idyll of all time; the four headed monster was dead. By the time of their official break-up, all of them had been working on solo projects that had started during their time spent in Rishikesh, India (1968), where they had been trying to get some spirituality in their lives through Transcendental Meditation.

During their time in India they composed almost the whole of The Beatles or White Album. And a song, here and there, would make it into their last two albums: Let it Be and Abbey Road. The tracks that weren’t utilized in any of the band’s records were, in a way, cornerstones of their respective solo careers.

So, musically, the White Album was the beginning of the end. As the boys started drifting apart, writing their own songs and working on them in the studio on their own. Even Ringo wrote his first song, “Don’t Pass Me By”, during that period.

In early 1968, The Band had put out their debut album Music from Big Pink. And it became quite the sensation, because of its solid grassroots sound and the vast display of Americana. We know that Americana has been a big contributor to pop culture for many decades. The harmonies and the different vocalists in The Band made for an interesting variety, standing out Levon Helm’s voice. Needless to say that many a rock band was influenced by their sound, including the Beatles (notably on the Let it Be album) and especially George. That influence would come through in All Things Must Pass, his opus magnum.

It was such the influence of The Band around that time, that American musicians were highly valued for their contribution and legitimization of the music that the British bands were making. The best example: Billy Preston in the last two Beatles albums. English rockers were looking up to and mingling with American musicians, left and right, and it set a precedent.

This is what Derek and the Dominos’ Bobby Whitlock says along those lines, regarding his early association with Eric Clapton: “When Eric had me living in his house, he had all the rhythm and blues, and real rock and roll and gospel music that there was in the whole of Great Britain; in his living room. Because I was the only guy there. They didn’t know about any gospel, rhythm and blues.”

In All Things Must Pass there’s an assembly of rock hard hitters: Eric Clapton, Billy Preston, Ringo Starr, Klaus Voormann, Peter Frampton, Dave Mason, Gary Wright, Gary Brooker, Jim Price, Bobby Keys, Alan White, the members of Badfinger, and some others whose participation, if any, wasn’t all that clear. But it was the players that would eventually become Derek and the Dominos (Eric Clapton, Bobby Whitlock, Carl Radle and Jim Gordon) the ones with the greatest influence and support during those sessions. As Eric Clapton put it himself: “we were the house band.”

All Things was the first rock album with a faith based theme to hit the big time, in a big scale. And it caused such impact in music, with the message of a higher ground reached through spirituality. Just the title alone, All Things Must Pass; quite a proverbial statement.

Because of that, Delaney & Bonnie‘s Delaney Bramlett was a defining figure in the midst of all the different players that came in contact with George. It was Delaney’s musical and personal mystique, of which Bobby Whitlock says: “He had that thing about him that attracted everyone; the gospel soul. You know, that gospel-rock. Everybody wanted to be around that for a little while: Leon, Joe Cocker, Duane Allman, Eric Clapton; he wanted it so bad that he wanted just to be a side man in our band. He stood back in the shadows. He wanted some of that to rub off on him.”

So Delaney Bramlett was, in fact, a big influence on the execution of things and helped George greatly in developing a general idea of what he wanted and how to put it in musical terms. He is also credited with teaching George how to play the slide.

But I want to talk about Bobby Whitlock, who was there in the epicenter of things, as an active player during the recording of George’s masterpiece. When we hear about All Things Must Pass, we usually hear about everybody else (Eric Clapton, Gary Wright, Gary Brooker, Billy Preston, etc.) but Bobby Whitlock. Bobby is an unsung hero, who has a lot to say as to what transpired in the recording studio during those sessions.

Even Beatles biographer, Nicholas Schaffner, didn’t set the record straight in his —otherwise awesome— book The Beatles Forever, when he says, “Harrison and Spector assembled a rock orchestra of almost symphonic proportions, whose credits read like a Who’s Who of the music scene: Ringo; Procol Harum’s Gary Brooker, Gary Wright, and Billy Preston (all on keyboards); Dave Mason and Eric Clapton (electric guitars); and dozens more. George himself painstakingly overdubbed his voice dozens of times, and credited the results to the George O’Hara-Smith Singers.”

And Gary Wright also leaves Bobby out when he talks in his autobiography about some of the musicians that played on the record: “The rhythm section shrank down to George, Klaus Voormann or Carl Radle on bass, Ringo or Jim Gordon on drums, Eric Clapton, and me on piano, organ, Wurlitzer piano, or harmonium.”

I read an interview some time ago, where a disgruntled Gregg Allman complains about the credit his brother Duane didn’t get from George for teaching him certain things. And even Delaney Bramlett talked about the possibility of claiming co-authorship for “My Sweet Lord”. Well, Bobby Whitlock was there steadily as a member of the house band and contributed with things he never got credit for. And up to this day he hasn’t raised his voice about it. Bobby has been badly underrated in his career, even when it was obvious that he was the soul of Derek and the Dominos. Just the way Levon Helm was the soul of The Band, because he was the only one with the first-hand knowledge of the American experience.

Since this is not a review of the whole album, I only chose some tunes I want to talk about. And for that I’m using some of Bobby’s comments and observations made during interviews, and from his book Bobby Whitlock: A Rock ‘n’ Roll Autobiography.

To open this great musical journey is the ballad “I’d Have You Anytime”, co-written with Bob Dylan. A tender tune, with an exquisite melody and an ethereal air to it that tell us, at the onset, that we’re listening to a special piece of music. Which reminds me of Revolver‘s opening track, “Taxman”, also by George that announces that we are listening to something different, right off the bat. According to Bobby Whitlock, the vocals were recorded live, with the exception of the second part.

The tune that follows is one that meant so much to George’s solo career, in so many ways, “My Sweet Lord”. A little hymn, intended for listeners everywhere to get some devotional time when listening to the radio in their car or at home, while running errands, doing their chores, or in the middle of their worldly endeavors. With a beautiful choral work by the O’Hara-Smith Singers, who were actually George, Bobby Whitlock and Eric Clapton. Infamously known for the fact that George was sued for plagiarism; which I’m not going to get into, because in the end he wound up owning the song he was accused of plagiarizing. To George’s own admission, he used Edwin Hawkins Singers‘ cover of the hymn “Oh Happy Day” as an inspiration for the melody. I personally find Glenn Campbell’s version that came out in April of that same year more in tune with it.

And then we have “Wah-Wah”, a significantly cool, original piece. “You’re giving me a wah-wah” or “you’re giving me a headache,” a complaint directed at Paul; very well articulated musically and lyrically. This is a Beatle song. Not because it sounds like a Beatles song, but because it is original, clever and the composer is clearly thinking outside the box. I enjoyed especially the Concert for Bangladesh‘s version of it. It goes in a continued motion, with that enhanced mountaintop effect produced by the Wall of Sound, which really comes in handy. And those horns that where a distinctive sound in some of George’s music since the White Album days.

The anthem “Isn’t it a Pity” (version one) has been one of my all-time favourites by George. A Beatles reject with a sententious —in the right sense— stance. Also on the proverbial side, with a hymnal aura to it. The orchestral arrangements, along with the slide guitar, the pump organ (played by Bobby Whitlock) and Ringo’s drums make all for an apotheotic delivery. Just like “Strawberry Fields Forever” and “Penny Lane” were released together 3 years earlier, “Isn’t it a Pity” came out as a double A-side single with “My Sweet Lord”.

“What is Life” is another track I want to cover here. A very well put together pop-rock tune with a nice instrumentation that was intended originally for Billy Preston. This is Bobby Whitlock’s account of it: “This was Derek and the Dominos with George playing the fuzzy lead part. Eric is playing his Stratocaster as the electric rhythm guitar and I’m on Hammond and one of the Garys (Brooker or Wright) is on the piano and Bobby [Keys] and Jim [Price] on horns.” There were seemingly some other musicians added later, but this was the basic unit for the production.

Next on the list is the soulful “Let it Down”. One of the most beautiful melodies on the record. The awesome way they build those crescendos to produce such a cathartic effect up to the chorus, of which Bobby Whitlock says: “I told him we ought to rock it right there when it says ‘Let it Down!’ George was completely open to everything that we had to say.” A strong, yet subtle, presence is the work that Billy Preston does on the piano, reminiscent of his work on “Far East Man”, in George’s Dark Horse album.

Then, “Run of the Mill”, a straightforward tune about personal relationships and interactions. Very telling of the times George was living with his old friends and musical partners, the other three. Everyone has choice/ When to or not to raise their voices/It’s you that decides. Outstanding work of George with the acoustic guitar.

“Beware of Darkness”, the opening track on the second disc (remember that All Things Must Pass is a triple album), and the second one with the proverbial enlightenment. A song of wisdom, with a beautiful melody, warning us about human nature (Watch out now, take care/Beware of the thoughts that linger/Winding up inside your head) and human condition (Watch out now, take care/Beware of greedy leaders/They take you where you should not go). “The first time I ever played a piano was on this song,” shares Bobby Whitlock.

And then, the heart-warming “Apple Scruffs”. A tribute to the diehard fans that stuck with the Beatles even after they were no longer fab. According to Bobby Whitlock, “that track was all George [acoustic and slide guitars; harmonica and all the vocal parts] except for the very old and tall metronome with a little effect added to it.” Also according to Bobby, this was George’s very first time playing harmonica. George seemed to be channeling Bob Dylan on this number.

“Ballad of Sir Frankie Crisp (Let it Roll)” is next. An upbeat song made as a tribute to the original owner and builder of George’s Friar Park mansion, Frank Crisp. It adds variety to the record and it gives freshness to it, in the midst of all the emotions, visions and thoughts projected on it. Alan White plays the drums on this one.

“Awaiting on You All” is, just as the title implies, one of the most welcoming tunes in the album, both melodically and lyrically. Another one with a strong spiritual theme of spiritual awareness. And to me it is also one of the highlights in the Concert for Bangladesh. This is what Bobby Whitlock says about its recording: “Eric and I are singing the background vocals. I’m singing the high part and he is singing the second part harmony. I really like the falsetto part. It all worked very well together.” The song was recorded live.

And we have the song that gives the album its title. “All Things Must Pass” is the piece where the influence of The Band is more pronounced. And George acknowledged that influence in an interview with Billboard magazine, in 2000. He even declared to Billboard that when he conceived the song he had Levon Helm’s voice in mind. The opening lines summarizes it: Sunrise doesn’t last all morning/A cloudburst doesn’t last all day. “I think I got it from Richard Alpert/Baba Ram Dass, but I’m not sure. When you read of philosophy or spiritual things, it’s a pretty widely used phrase,” he said about the source of inspiration for those verses. Another piece with the proverbial wisdom; George was only 26 when he wrote it.

“Art of Dying” is an interesting piece. Very different to the rest of the repertoire covered in the album. “Eric kicks this rocker off with some killer wah-wah guitar!” says Bobby Whitlock. A tune in the same style of “Savoy Truffle” or even “Bangladesh”, but infused with what it feels like a messianic air of prophecy. There’ll come a time when all of us must leave here/There’s nothing Sister Mary can do, will keep me here with you. Bobby again: “The feel of this song reminds me of a horse at full gallop.”

Last, but not least, “Hear Me Lord”. In tune with the spirit of the album, we couldn’t close with a better song. A sincere plea that George followed up 3 years later —in a grand scale— with “Give Me Love”. One thing we can say about George, is that he was passionate about his beliefs and he wanted to include everybody. This song doesn’t make a distinction as to what kind of higher power he is reaching out to, which anybody can identify with. The arrangements and instrumentation are great and the voice and lyrics magnificent. “George is playing some great guitar and singing all of the background vocals,” reports Bobby Whitlock.

An interesting fact that was pointed out by Nicholas Schaffner, is that George’s and John’s first album —after the Beatles— came out almost simultaneously. And even though both are co-produced by Phil Spector, they went in opposite directions. “In stark contrast to the mystical affirmation of All Things Must Pass, John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band shows John striving to demolish every icon in sight —be it Krishna, Jesus, sex, dope, or the Beatles,” observed Schaffner.

There are quite a few people that don’t agree, but I actually think that Phil Spector’s Wall of Sound was a good occurrence throughout the record. At least on songs like “Isn’t it a Pity”, “My Sweet Lord”, “Wah-Wah”, “Awaiting on You All”, “What is Life” and “Art of Dying”. Journalist Jody Rosen reviewed All Things Must Pass in 2001 for The New York Times, and he refers to “Hear Me Lord”, “Art of Dying” and “Wah-Wah” as examples of Spector’s merit in transforming them on an “operatic scale.”

But regardless of who the credit is going to for what, it is a fact that All Things Must Pass stands out as one of the greatest albums in rock history, both qualitatively and quantitatively. And it was also George Harrison’s personal triumph in overcoming the adversity of being in John’s and Paul’s shadow for so long.

Melody Maker‘s Richard Williams said that All Things Must Pass was “the rock equivalent of the shock felt by pre-war moviegoers when Garbo first opened her mouth in a talkie: Garbo talks! —Harrison is free!” Nobody saw it coming. That’s how much George was breathing on his own at this point. And he was unstoppable.